Big recommendation for Alex Ross' The Rest is Noise, a history of 20th century classical music. I enjoyed the first 2/3rds of it immensely. It did a lot to revise my formerly sloppy references to things like "atonal" or "12-tone" music. I know much better now what is and what ain't. It even did something to get me excited about the idea of composition, something I've never thought about with interest before. I've been thinking about going back to school to study music, and it's become clear that I'd probably have to learn a lot of theory to get into graduate school, so I've been thinking about trying to do that - and now, with the idea that maybe I'd write some music, learning theory doesn't seem that awful.

The best aspect of the book is its biographical portraits. It's great fun to read about the wars between what you might call the musical idealists and the musical realists - those who insist there need to be absolute laws governing the composition of music, and those who basically say they know good music when they hear it. It's great to see a whole spectrum, from one extreme to the other, among the great composers of the century.

I was touched by the story of Shostakovich, whose string quartets I've come to love over the last couple of years. He's quite a tragic figure, living a life of apparent terror, suffering innumerable humiliations, and vilified by right-thinking people, effectively for choosing humiliation rather than torture and death, or the same for his family. But then I've got Lenin and Stalin on the brain after reading Koba the Dread (Martin Amis), and after thinking of our country's own active torture chambers.

A Shostakovich string quarter movement:

Two problems with the book: First and foremost, it leaves out the audience, or at least buys in, to some degree, to a snide attitude toward it. Many 20th century composers, particularly once they discovered no one wanted to listen, insisted that they didn't care if people listened, or would even rather they didn't. But I don't see why Ross should play along with this being even vaguely acceptable. I think it's rather horrid. It seems to me that as radically as music changed in this century, the audience changed just as radically, and that's of central importance to the story of music. It seems to be an aside for Ross, and I think that gives listeners short shrift. Without the listener, one must ask, Who Cares? If Stockhausen and Boulez diddle themselves to the end of time, who cares? I can find auto-diddlers in just about every adolescent bedroom in the country, and none of the diddlers' fantasies, I think, deserve my attention. Without a willing ear, music is just air, shaking.

I should repeat, Ross does mention these tensions around the audience, but ultimately he lets it drop, particularly in the last part of the book, when he makes a headlong rush through the European avant-garde and experimentalists. It seems to me every sentence should end with, "and no one heard it," or "and it was performed once for 12 people." Not true of all of the avant-garde works, I know, but not that far off either. Instead, we play along with the pose of seriousness when Stockhausen tells his players to reverberate with the universe, or whatever.

One example of the negative effect of Ross' casual treatment of the audience factor is the way that Darmstadt, the Mecca of the atonalists, is given the same sort of treatment as Paris or Berlin is earlier in the book. It was and is a place where self-pleasing composers go to play their music for other self-pleasing composers. It is a club. It is a conference. Paris is not a club. Berlin is not a conference. They are not these things because they are not just meeting places for composers - they are meeting places for composers and audiences. And after all, isn't it the audience Ross is writing the book for? I want to know, always, what's in it for me?

That's getting a bit confused - at any rate, the second complaint: The biographical fun peters out around 1960. The last third of the book is pretty dry at times.

One odd thing about the book: serious overload on Britten. Ross seems totally fascinated by the guy and by his man-boy love. He takes us on a complete step-by-step tour through three entire Britten operas. Maybe it is my imagination, but his treatment of Britten seems to be the longest of any treatment in the book. I guess I need to listen to Britten, but meanwhile, I get the impression Ross wants to write about homosexuality and 20th century music, and it sounds like he'd have a lot of interesting things to say about it.

Sonntag, Oktober 26, 2008

Sonntag, Oktober 05, 2008

Funny thing

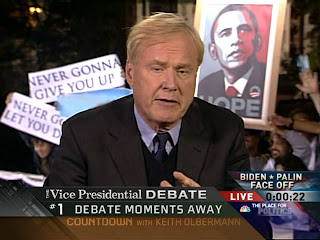

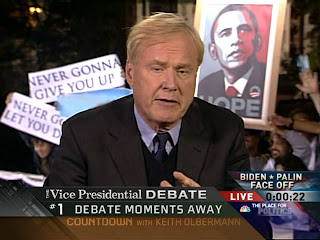

It seems coverage of the recent VP debate got rickrolled.

It's not the first time somebody's held up a funny sign for the camera during an ostensibly serious news event. Perhaps, then, it's not an historic moment, but it does seem potentially to be an historically memorable expression of the Zeitgeist. It seems to say something important about what Generation Y thinks is funny, which is a funny thing, or what they think is serious, which is a serious matter.

I recently read an interview with Woody Allen in which he noted that today's smart kids appear to have the same taste as today's dumb kids, preferring the lowest forms of humor to anything approaching art, bored by Bergman and in raptures over one idiot kicking another idiot in the nards on Jackass. I say he "noted" it, rather than "complained," because the man's smart enough to know that what's past is past - no vehemence of nostalgia can recapture a dead era. One commenter on the interview, while misunderstanding this latter distinction, had an interesting reply: You, Mr. Allen, don't understand our humor today - everything is ironic, so part of the fun of watching someone getting kicked in the nards is the fact that we know that's a stupid thing to find funny. Well okay, but isn't that rather miserably fin de siecle? If we have nothing genuinely funny or engaging or interesting today, the distinction between funny or engaging or interesting and ironically funny or engaging or interesting is bound to be lost on the next generation. This is exactly what decadence, in its proper historical sense, looks like. It is irony so universal as to become cynicism.

That said, I don't mean to imply that the sign-holders behind Chris Matthews were missing the real importance of the moment. It is impossible to disentangle the serious from the entertaining in our contemporary media politics. Certainly the VP debate was, in some genuine and important ways, fake and unimportant. It was a joke, and America was the butt. In short, I can't argue that we aren't in fact at the end of the Enlightenment Era. It is the end of an era, the decadence of something grand, and perhaps that's funny, in a way.

It's not the first time somebody's held up a funny sign for the camera during an ostensibly serious news event. Perhaps, then, it's not an historic moment, but it does seem potentially to be an historically memorable expression of the Zeitgeist. It seems to say something important about what Generation Y thinks is funny, which is a funny thing, or what they think is serious, which is a serious matter.

I recently read an interview with Woody Allen in which he noted that today's smart kids appear to have the same taste as today's dumb kids, preferring the lowest forms of humor to anything approaching art, bored by Bergman and in raptures over one idiot kicking another idiot in the nards on Jackass. I say he "noted" it, rather than "complained," because the man's smart enough to know that what's past is past - no vehemence of nostalgia can recapture a dead era. One commenter on the interview, while misunderstanding this latter distinction, had an interesting reply: You, Mr. Allen, don't understand our humor today - everything is ironic, so part of the fun of watching someone getting kicked in the nards is the fact that we know that's a stupid thing to find funny. Well okay, but isn't that rather miserably fin de siecle? If we have nothing genuinely funny or engaging or interesting today, the distinction between funny or engaging or interesting and ironically funny or engaging or interesting is bound to be lost on the next generation. This is exactly what decadence, in its proper historical sense, looks like. It is irony so universal as to become cynicism.

That said, I don't mean to imply that the sign-holders behind Chris Matthews were missing the real importance of the moment. It is impossible to disentangle the serious from the entertaining in our contemporary media politics. Certainly the VP debate was, in some genuine and important ways, fake and unimportant. It was a joke, and America was the butt. In short, I can't argue that we aren't in fact at the end of the Enlightenment Era. It is the end of an era, the decadence of something grand, and perhaps that's funny, in a way.

Abonnieren

Kommentare (Atom)